Paper Study - ABC Accelerate Brake Control

10 Mar 2020** This is a study & review of the Opera paper. I’m not an author.

ABC

Intro

- A new explicit congestion control protocol for network paths with wireless links

- Existing explicit control protocols (XCP, RCP, specify a target rate for sender and receiver) problem

- designed for fixed-capacity links, no good performance in wireless network

- require major changes to packet header, router, endpoints to deploy

- Simple mechanism: a wireless router marks each packet with either accelerate or brake with two bits, sender receives this marked ACK to enlarge and shrink sending window size

- Accurate feedback & measurement for link condition

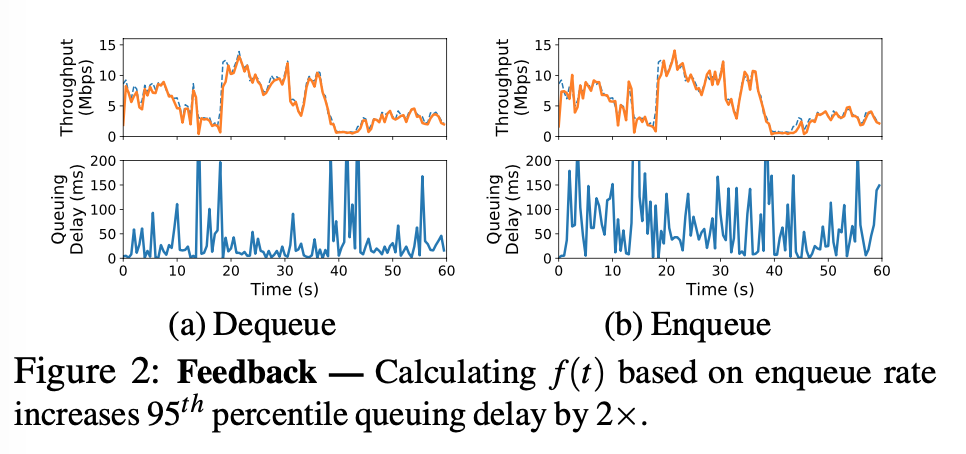

- XCP, RCP compares enqueue rate with link capacity

- ABC router compares dequeue rate with link capacity, because dequeue rate is a more accurate indication of how many packets will be arriving in next RTT

- Can be deployed on existing explicit congestion notification (ECN) infrastructure

Motivation

-

Main challenge: wireless link rates vary largely and rapidly, hard to achieve high throughput and low delay

-

End-to-end congestion control

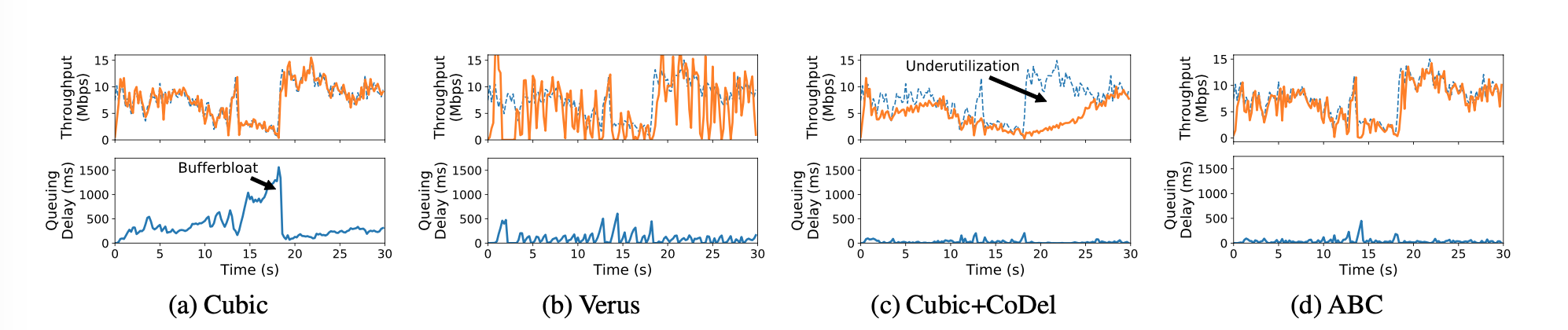

- Cubic (a)

- Rely on packets drop to infer congestion.

- Large buffer, long queue, large delay

- BBR

- Uses RTT and send\receive rate to infer congestion condition

- can cause underutilization

- Verus, Sprout (b)

- Uses a parameter to balance aggressive(large queue) and conservative(low utilization), tradeoff

- Cubic (a)

-

Active Queue Management (AQM) schemes

- RED, PIE and CoDel (c)

- signals congestion, but do not signal good link condition

- underutilization

- RED, PIE and CoDel (c)

-

Deployment

- XCP, RCP requires modification of header, router, endpoints. Not very compatible with existing infrastructures, some router drops packets with IP options, TCP options is problematic for middle-box (firewall, etc) or IPSec

- Fairness to older routers

-

Goals

- Control algorithm for fast-varying wireless links

- No modifications to packet headers

- Coexistence with legacy bottleneck routers

- Coexistence with legacy transport protocols

Design

-

ABC senders receives an

- accelerate ACK, increases congestion window by 1, effectively sending 2 packets, 1 for ACK & 1 for window size increase

- brake ACK, decreases congestion window by 1, effectively stops sending packets in response to the decrease in congestion window size

-

effectively this scheme can double (all accelerate ACK) or zero (all brake ACK) the current congestion window in one RTT

-

Target rate is calculated with $tr(t)=\eta\mu(t)-\frac{\mu(t)}{\delta}(x(t)-d_t)^+$, where $μ(t)$ is the link capacity, $x(t)$ is the observed queuing delay, $d_t$ is a pre-configured delay threshold, $η$ is a constant less than 1, $δ$ is a positive constant (in units of time), and $y^+$ is $max(y,0)$.

if x(t) < dt: ## queueing delay is low target = ημ(t) ## η = 0.95, slightly below bandwidth for delay reduction else: ## queueing delay is higher than threshold target = ημ(t)-(μ(t)/δ)(x(t)-dt) ## reduce the amount that causes the queueing delay to decrease to dt in δ seconds -

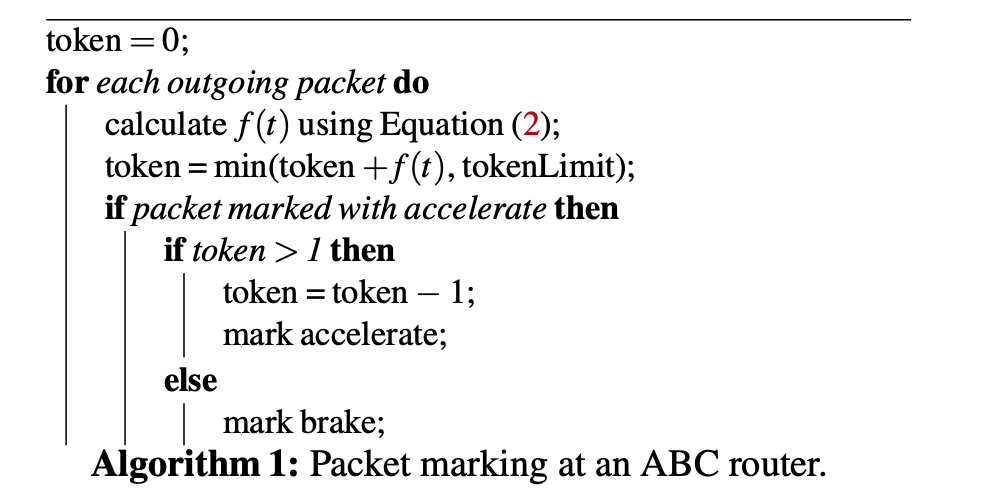

Marking (how much should be marked accelerate) fraction is calculated with $f(t)=min(\frac{tr(t)}{2cr(t)}, 1)$, where $cr(t)$ is the dequeue rate.

-

enqueue rate vs dequeue rate:

- $f(t)$ is calculated with every outgoing ACK, thus granting quicker adjustments to the network condition than periodical schemes (XCP, RCP) with the following algorithm to ensure no more than a fraction of $f(t) $ of packets are accelerate ACKs.

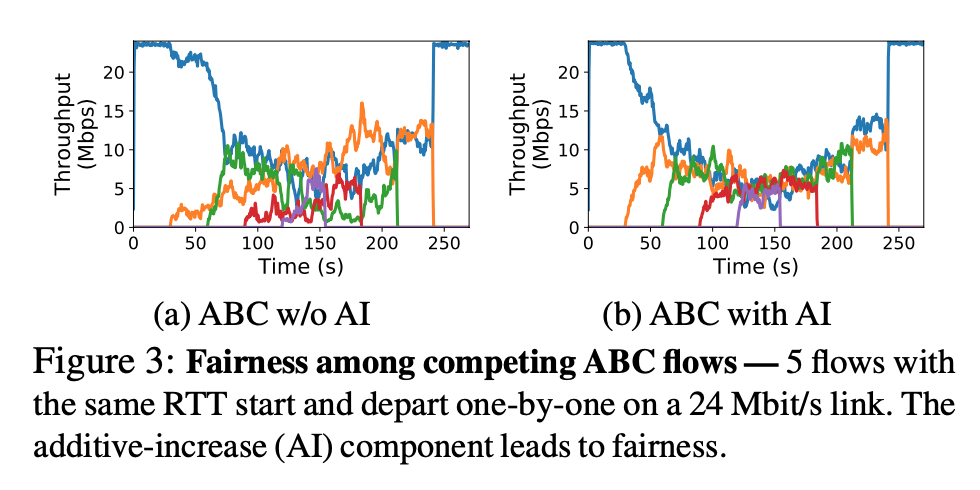

- Fairness is achieved with the following algorithm $w\leftarrow \begin{cases}

w+1+1/w \text{ , if accelerate}

w-1+1/w \text{ , if brake}

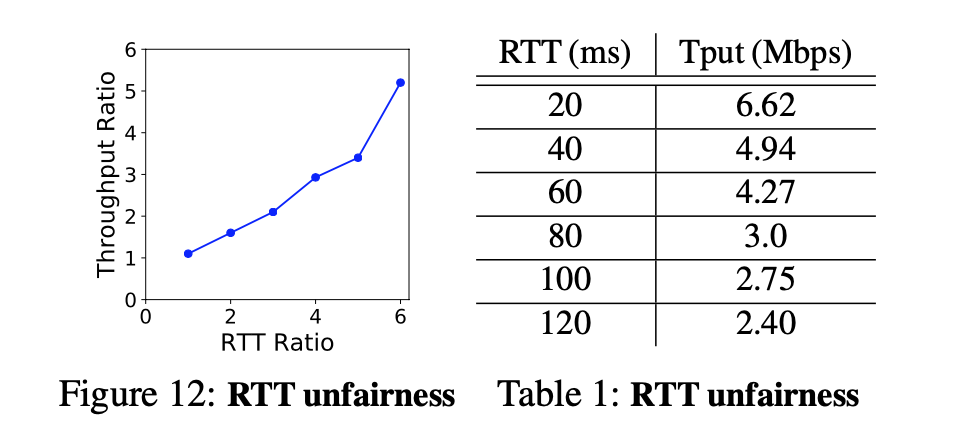

\end{cases}$ , which includes additive increase (AI), but still suffer from RTT unfairness: the throughput of a flow is inversely proportional to its RTT, like Cubic.

Deployment

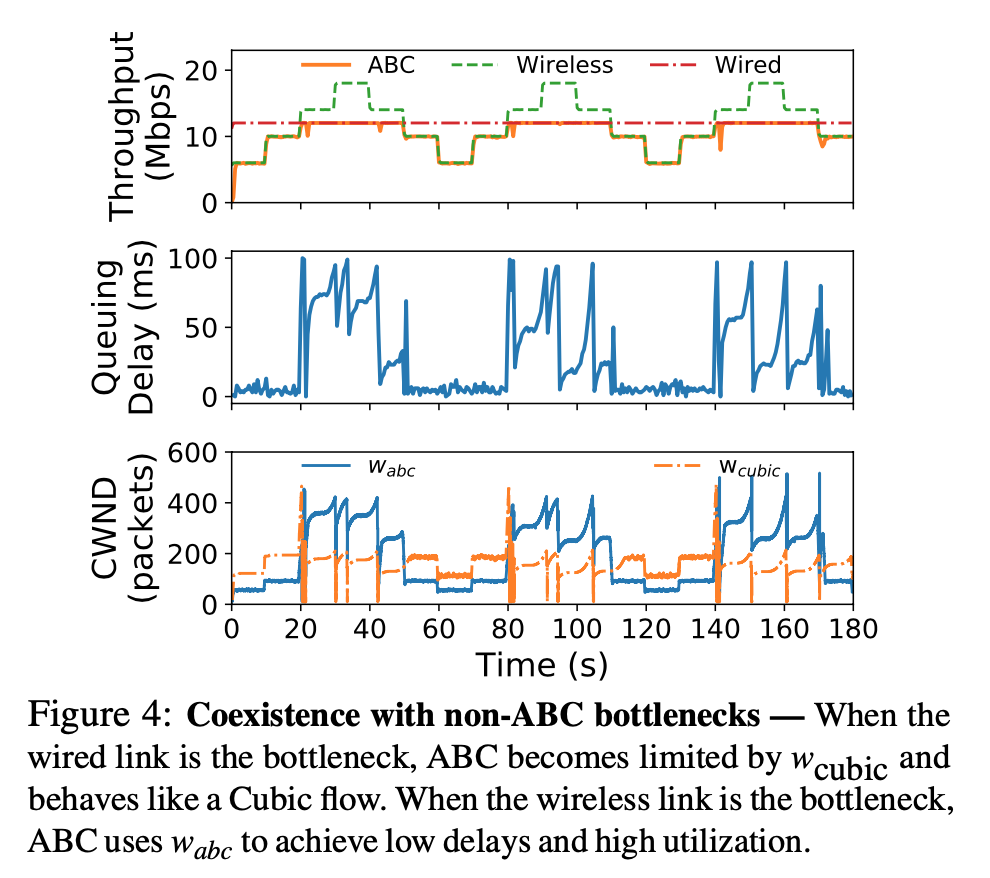

- coexistence with non-ABC routers: must be able to react to traditional congestion signals (drops or ECN) $\rightarrow$ keeping two link rates, one for ABC rate, not for non-ABC rates, use smaller one

- problem: when non-ABC router is bottleneck $\rightarrow$ ABC rate continuously grow

- solution: caps both ABC rate and non-ABC rate at 2X # of packets in-flight

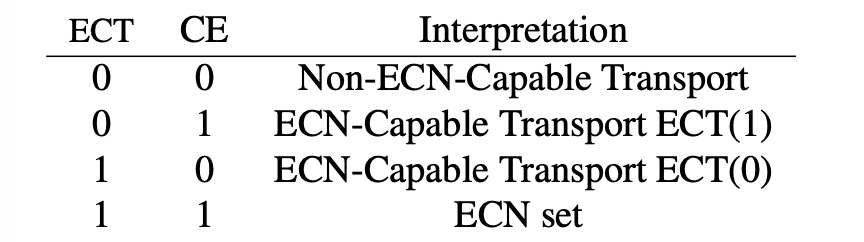

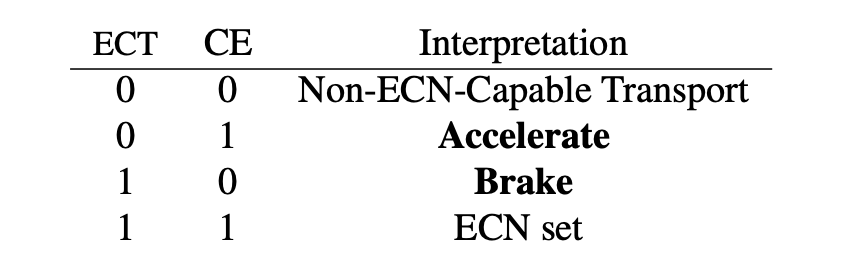

- Protocol implemented with ECN bits

- legacy ECN bits

- ABC bits

- Only needs to modify receiver software

Discussion

- Delayed ACK: uses byte counting at the sender, sender in/decreases its windows by the new bytes ACKed, keeps track of state (acc/brake), once state changes, sends a ACK for state change

- Lost ACK: ABC can handle lost ACK

- ABC routers do not change incoming ECN marks: because ECN does not convey ABC accelerate/brake information, ECN will slow down adjustment. When ECN is small in fraction, adjustment loss is small. When ECN is large in fraction, non-ABC router becomes bottleneck and sender will not use ABC window and rates.

- ECN routers can overwrite ABC acc/brake bits, but will not be a big problem as previous entry suggests

Eval

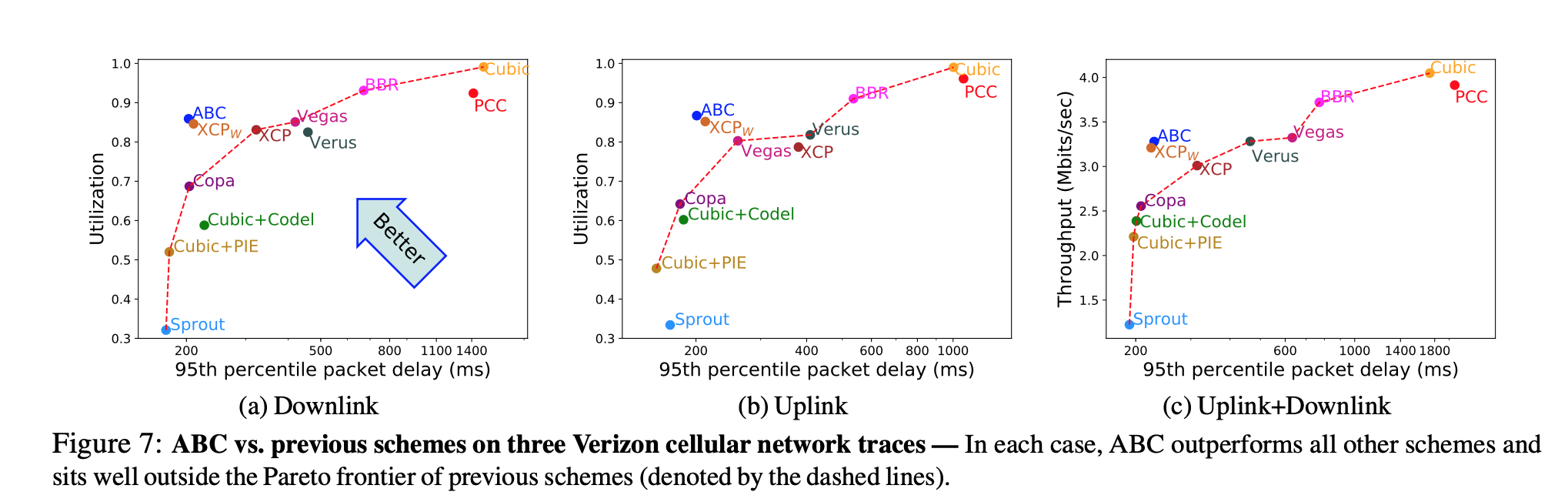

- On Verizon cellular network, ABC outperforms other protocols

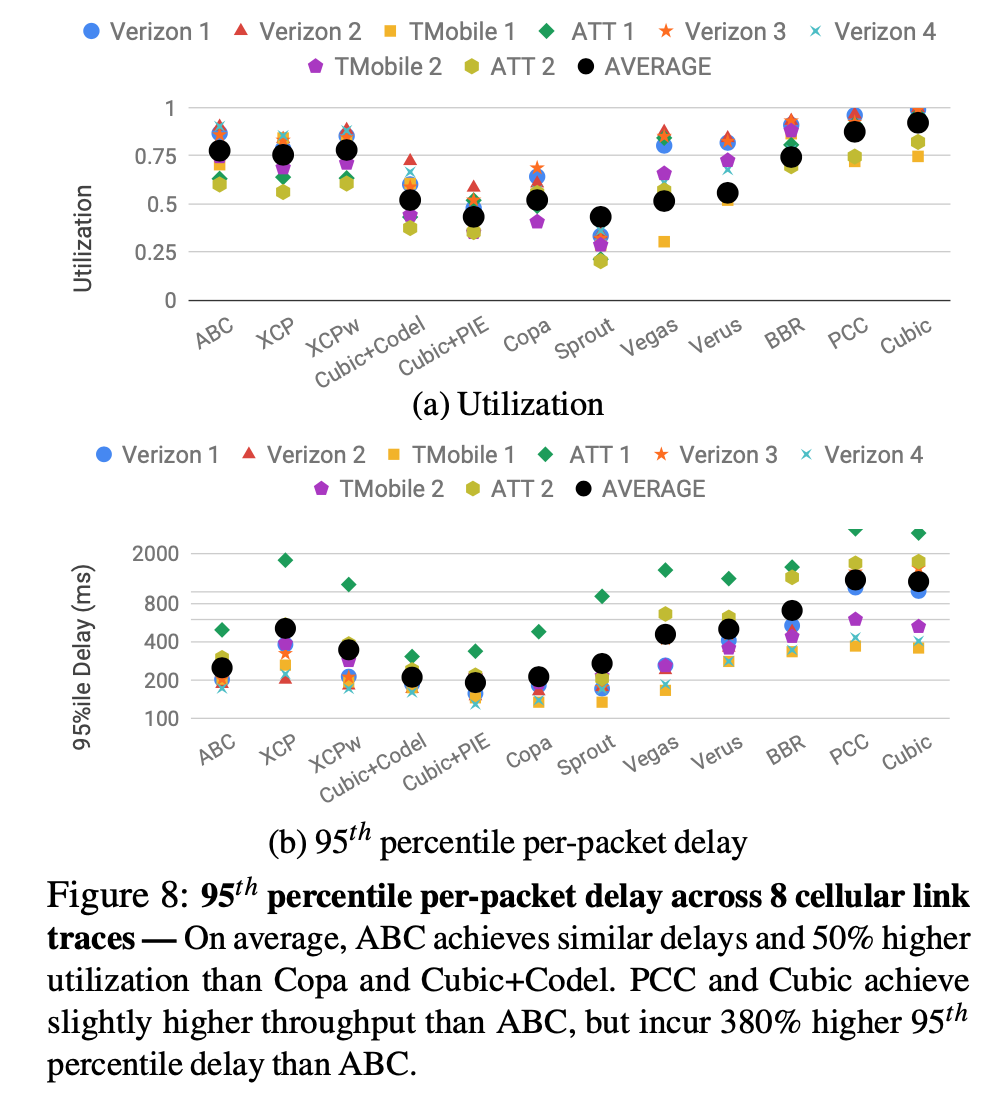

- Tested on 8 different cellular networks against other explicit congestion control scheme: PCC/Cubic achieves higher utilization, but they are considerably higher in delays

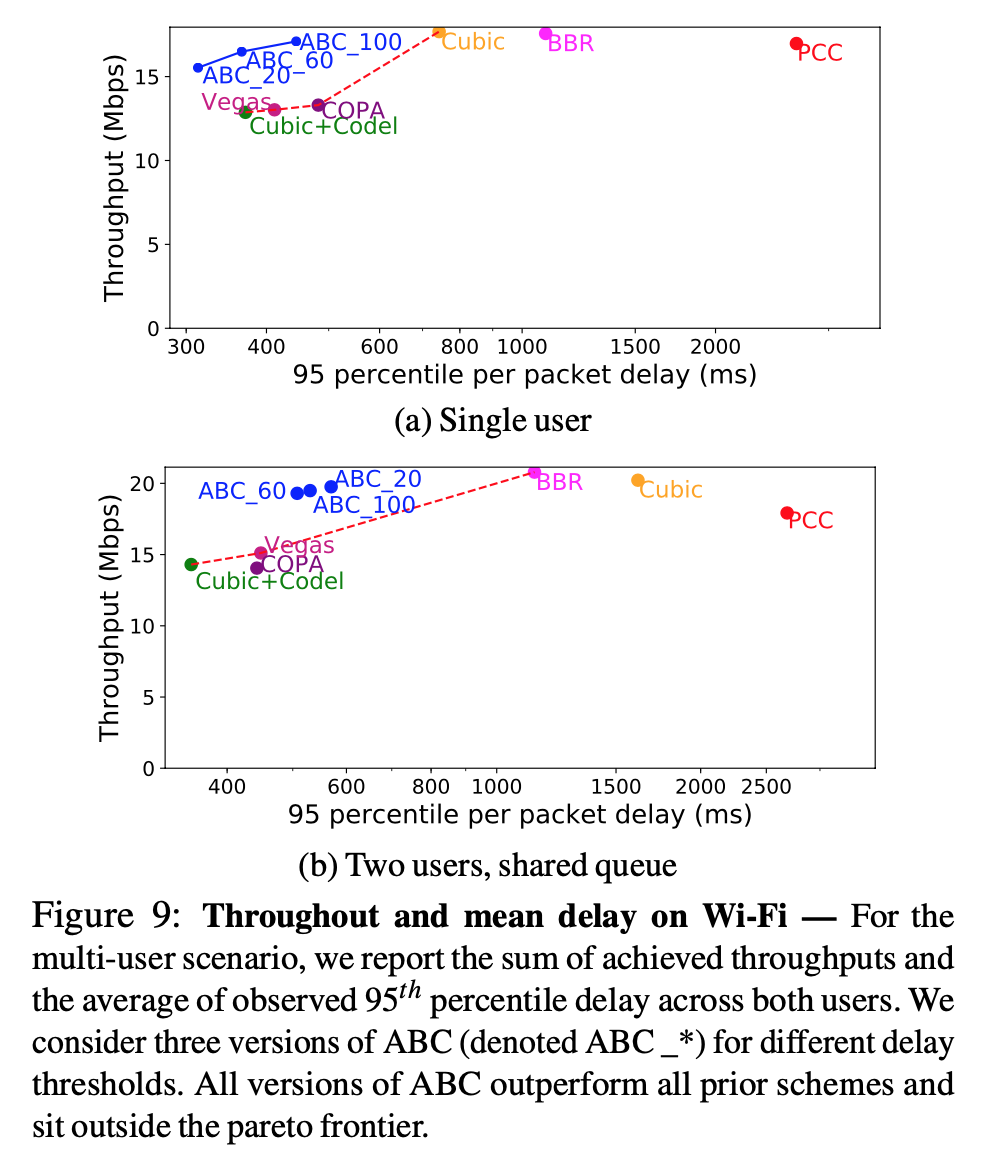

- Performance over WiFi with different delay threshold

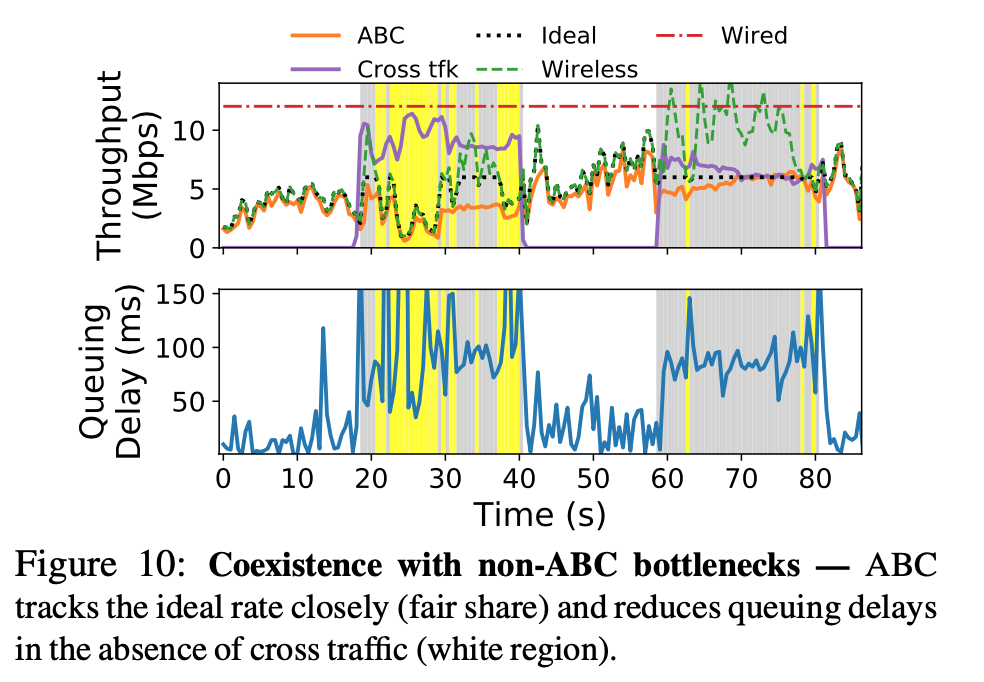

- black doted line is ideal rate, closely matched with orange line (ABC), low delay when no cross traffic, matches wireless in yellow region (wireless is bottleneck), and ideal in gray region (wired is bottleneck)

- ABC suffers from RTT unfairness, similarly to Cubic

Conclusion

A new explicit (accelerate/brake) congestion control protocol for network paths with wireless links, which is deployable.

a. target rate

target rate is enqueueing rate in 1 RTT

at $T_{RTT=0}$, dequeueing rate $cr(t)$, $f(t)$ of accelerates will comes back with $2*f(t)$ packets in the next RTT

at $T_{RTT=1}$, $tr(t) = cr(t)2f(t)\rightarrow f(t)=\frac{tr(t)}{2*cr(t)}$

For example, when we want steady state; $tr(t)=cr(t)$:

$tr(t)=cr(t)2f(t) \rightarrow f(t)=\frac{tr(t)}{2*cr(t)}=\frac{1}{2}$

$f(t) = 1/2$ to maintain current rate

**b. why not steady state ** percentage change

Because

- wireless link conditions change by a largely and quickly, very unsteady by nature.

- they want to have quick adjustment to the rate, where schemes like DCTCP still is periodical (by grouping ACKs together for analysis), which is slow in adjustment in their opinion

c. link estimation

Who does the job? 802.11n access point (AP) router

Two cases: single user, multiple users

Link rate is defined as the “potential throughput” of the user (e.g. MAC of a WiFi client)

possible solutions

-

use physical layer bit rate (depends on modulation and channel code), but will overestimate link rate (does not count delay for additional tasks, e.g. channel contention, retransmission…)

-

use fraction of time that the router queue was backlogged $\rightarrow$ link underutilization, but WiFi MAC packet batching is problematic for this approach. Batch builds up while waiting for ACK for last batch, but does not indicates that the link is fully utilized

Batching

In 802.11n, data frame (MPDUs) is transmitted in batches (A-MPDUs).

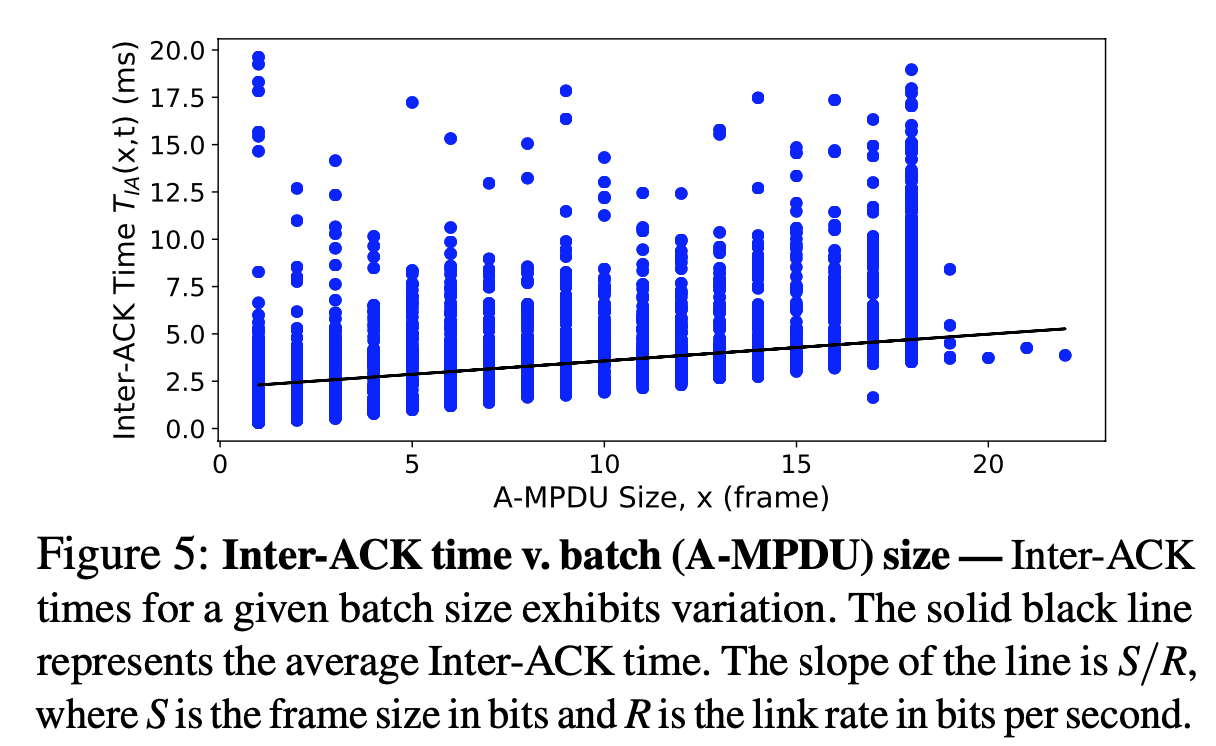

Current Dequeue Rate can be estimated by \(cr(t)=\frac{b*S}{T_{IA}(b,t)}\) where $b$ is a smaller batch size $b<M$ (router might send a b-sized batch when not having enough data to send a M-sized full batch ), $M$ is full-sized batch size, frame size S bits, $T_{IA}(b,t)$ is ACK inter-arrival time (time between receptions of two consecutive block ACKs)

When user is backlogged, $b=M$, the estimation equals link capacity.

When user is not backlogged, $b<M$, calculate $T_{IA}(M,t)$, as if the user is backlogged and had sent M frames.

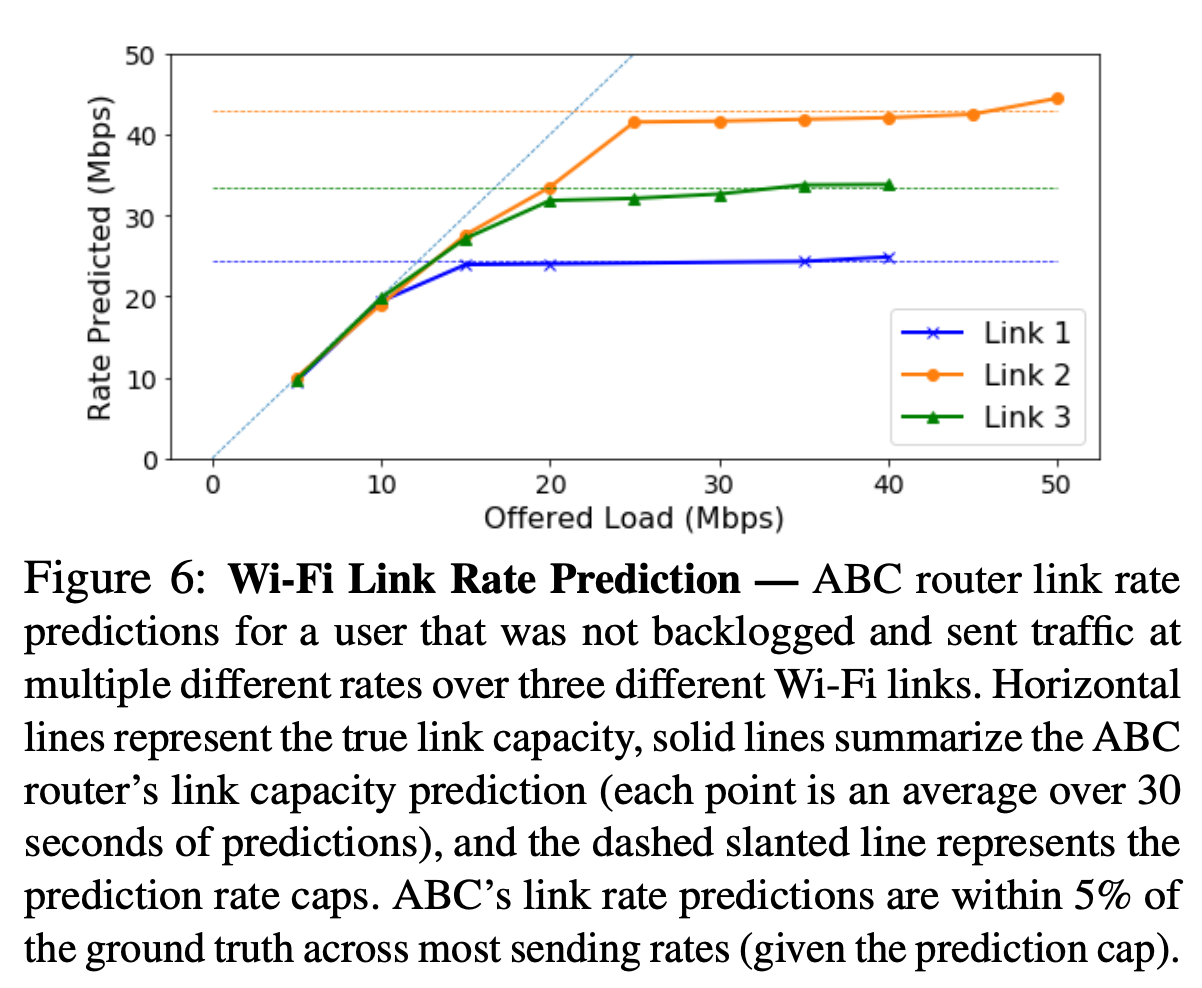

Thus Link Capacity can be estimated by \(\hat{\mu}(t)=\frac{M*S}{\hat{T}_{IA}(M,t)}\)

Now the problem becomes estimating ACKs interval time $T_{IA}(M,t)$.

ACK interval time = batch transmission time + “overhead” time (e.g. physically receiving ACK, contending for shared channel, transmitting physical layer preamble…) $\rightarrow$ \(T_{IA}(b,t)=\frac{b*S}{R}+h(t)\) where $h(t)$ is overhead time, R is bitrate for transmission

- for same batch size, interval vary due to overhead

- slope of the line is $S/R$

Thus the ACK Interval Time can be estimated by \(\begin{align*} \hat{T}_{IA}(M,t) & = \frac{M*S}{R}+h(t) \\ & = {T}_{IA}(b,t) + \frac{(M-b)*S}{R} \end{align*}\) Calculation on every batch transmission, pass through a weighted moving average filter over time T to smooth out. They used T=40ms.

horizontal dashed line: true link capacity

solid line: ABC prediction, very close to true capacity

dashed slope line: ??

Multiple users**

Different users have their own batch size M and transmission rate.

Two scenarios:

- per-user queues

Each user calculates a separate link rate estimate. Notable: 1. ACK interval time is on a per-user basis; Overhead time $h(t)$ now includes time when other users are scheduled to send packets. Fairness is ensured.

- single FIFO queue

Router calculates single aggregate link rate estimate. Notable: inter-ACK time for all user ACKs, regardless of which user this ACK belongs to. Use aggregate link rate to guide target rate, and control accelerate-brake ratio. (Fairness not ensured?)

Cellular Networks

Each user has its own queue and link rate. 3GPP provides how to use scheduling information to calculate link rate.

d. why using only two states

No room in TCP header, can’t use IP/TCP options $\rightarrow$ repurpose ECN bits and ECN bits can only be repurposed into two states. Two states are sufficient to handle the adjustment when the number of packets are large enough, because one accelerate will cancel out one brake, thus achieving steady state is not hard.